-

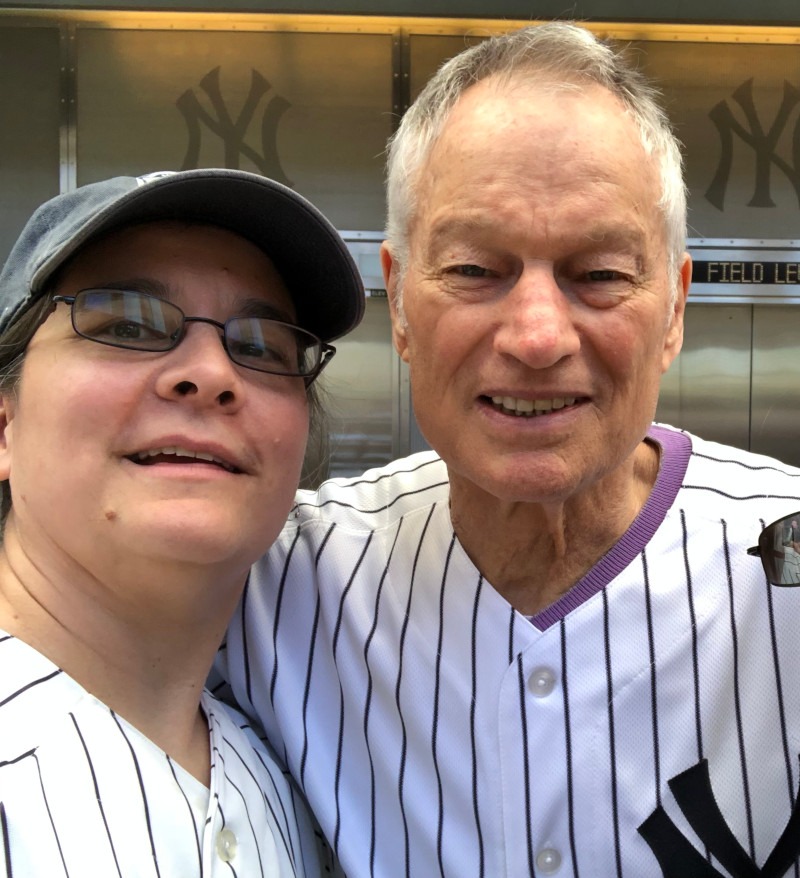

Flag Day (2024 World Series Game 3)

Well, the Yankees often provide us thrills on the field, but this is about how they provided me and 80-ish other folks a thrill that was literally on the field. I was one of the flag handlers for the National Anthem on the field yesterday. I don’t know when the “giant flag in the outfield”…

-

Adios El Tiante

I was lucky to meet Luis Tiant many times, because he was so easy to meet if you were around the Red Sox. He was not shy of the public, and was one of most outgoing and friendly people I’ve met in professional baseball. The first time I met him was when I took a…

-

Book Review: Why We Love Baseball by Joe Posnanski

I have not had the time to do a lot of book reviews here on the blog in the past ten years or so, but when I saw Joe Posnanski was titling his latest book Why We Love Baseball, I knew it would be a moral imperative for Why I Like Baseball to review it….

-

SABR 51: Chicago

It’s been a few years since I had the time and brainpower to write up one of these recaps of a SABR convention! Of course there were no conventions for a few years in the pandemic, so last year’s one in Baltimore had been delayed twice. This year was Chicago, where we returned to the…

-

My 2004 Interview with Jim Bouton

Perhaps it’s a bit macabre, but the thing that motivates me to dig out my old notes and interview transcripts from 2000-2005 is when a player or coach I interviewed dies. I suppose it is inevitable that a bunch of middle-aged and older men I talked to ~20 years ago would be reaching the ends…

-

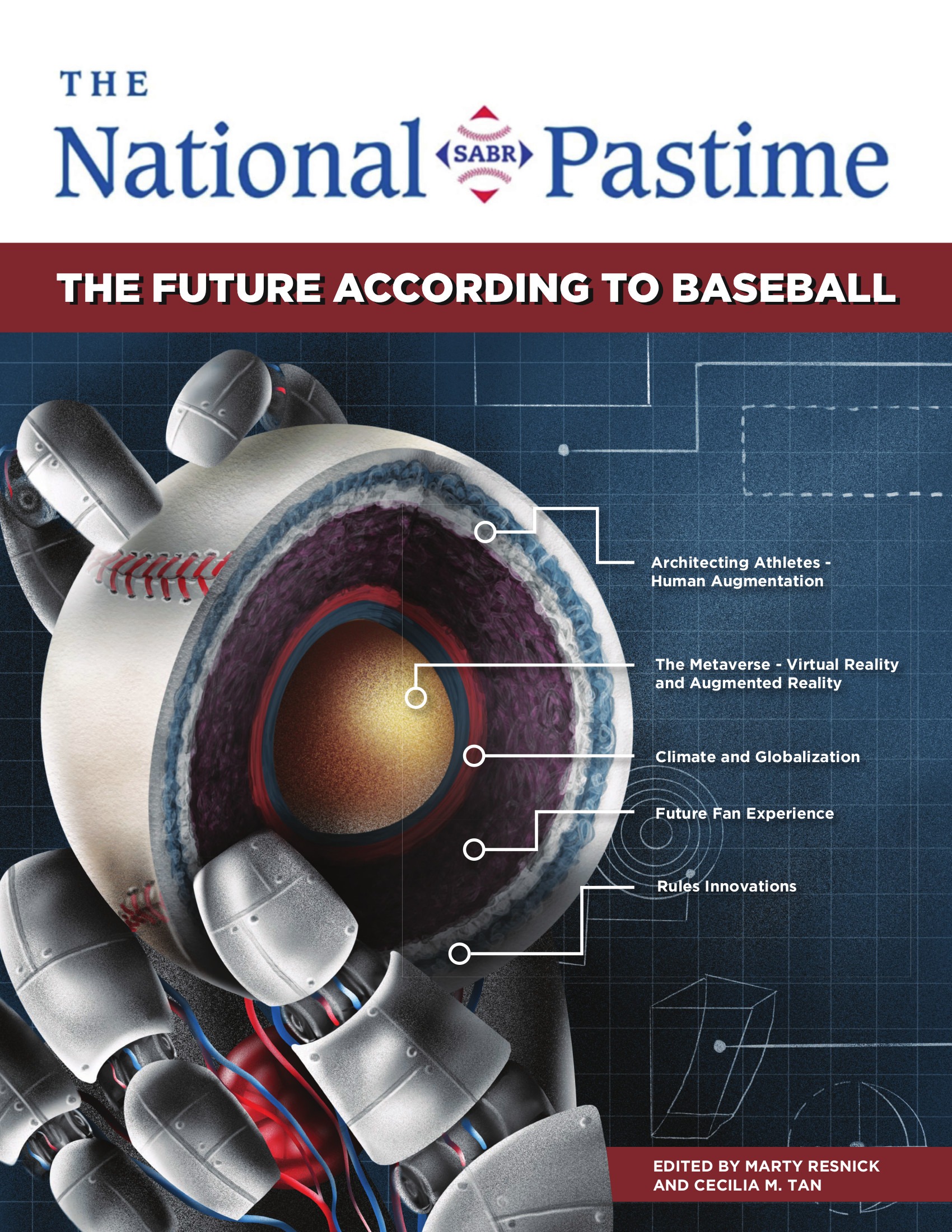

New baseball science fiction short story (free to read)

I have a new short story, free to read online at SABR.org! It’s a piece of near future science fiction told from the point of view of a female baseball pitcher making her debut on the mound at Fenway Park. It’s one of the few times I’ve gotten a chance to mix my baseball writing…

Why I Like Baseball

AN ONLINE JOURNAL OF BASEBALL ENTHUSIASM, by CECILIA TAN